Ever since our country was founded, local, state and federal governments have acknowledged the notable economic contributions of agriculture. Here in the Midwest, even if you were not a farmer, you grew up hearing your parents say, “If the farmers do well this year, our town will have a good year, too,” since most farmers’ dollars were spent first within their own communities.

According to Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP), agriculture contributes $88.3 billion annually to Wisconsin’s economy and provides employment for 827,000+ people (with every Ag-related job supporting an additional 1.46 Wisconsin jobs). 1

Wisconsin is ranked third in the nation for potato production and processing vegetables acres harvested (and second in processing production and value) according to the USDA Vegetables 2014 Summary released January 2015.

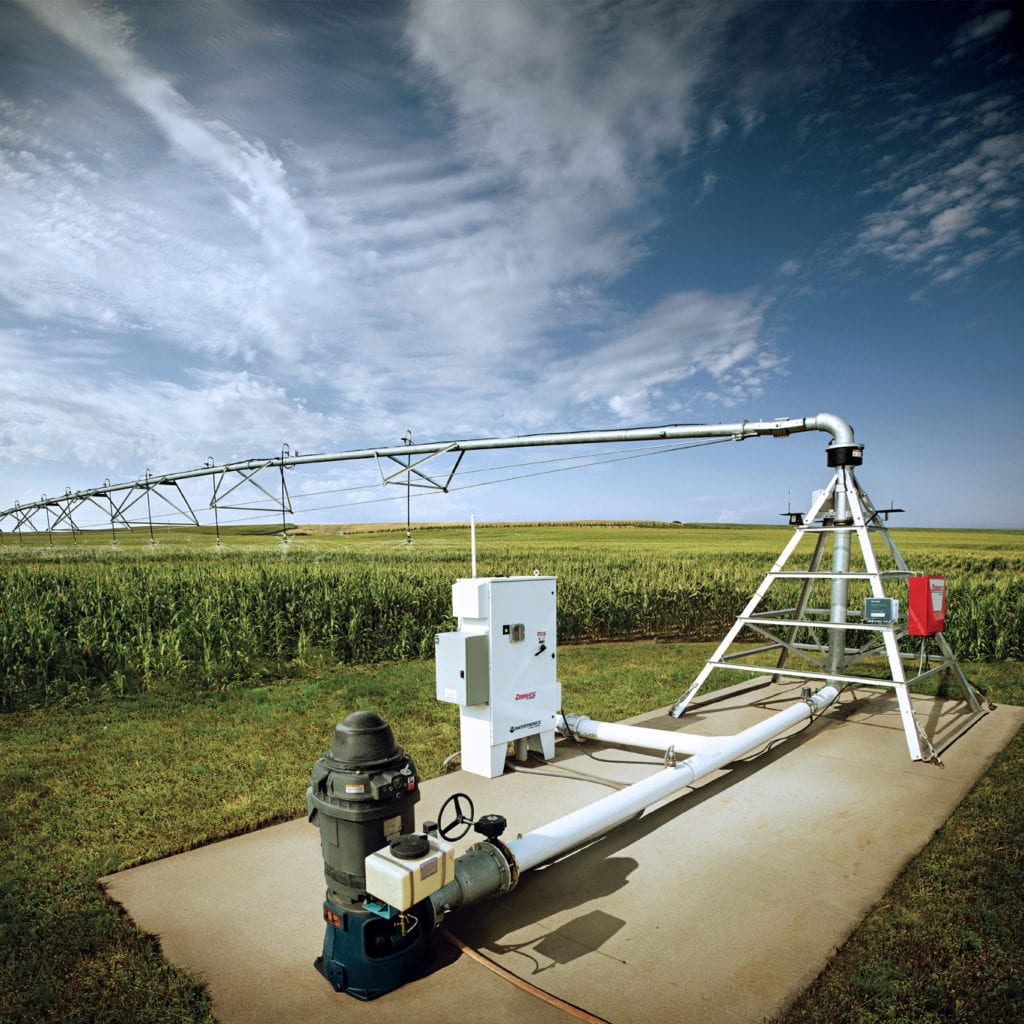

Much of that is attributable to the Central Sands region, where the advent of irrigation back in the 1940s transformed what was a non-farming area due to the sandy soils, which do not readily retain water, into a megalithic growth in potato and processing vegetable production.

SIDE BENEFITS

That growth also attracted major processing companies like Del Monte, McCain Foods USA and Seneca Foods Corporation to the area along with potato specialists, dehydrating companies, fresh packing warehouses and more.

These were followed by crop input, farm equipment and irrigation equipment dealers, fuel suppliers, plus service providers such as agricultural consultants, banking, insurance and legal entities. The building trades boomed as well, since farmers required more and more storage, processing, equipment and office facilities.

The dairy industry burgeoned simultaneously with the potato and vegetable industry because irrigation led to a more steady supply, which helped insure nutrient-rich feed for milk production.

ENTER HIGH CAPACITY AG WELLS

Additionally, as farms expanded due to the ability to farm land previously not suited to crops, more water was required for irrigation. That led to the development of high capacity agricultural wells, which provided the gallons per minute needed to run larger irrigation systems. This, in turn, gave rise to the need for more well drillers and related suppliers.

Potato and processing vegetable crops are particularly dependent on high capacity wells for a dependable supply of irrigated water, not only to grow but to maintain appearance (shape, color, consistent size and blemish-free), overall quality (taste, sweetness, turgidity to allow them to remain upright, uniform ripeness) and furnish nutrients for human and animal consumption.

DAIRY’S STORY

High capacity wells opened the door for larger dairy operations, providing the ability to water livestock on a steady basis, thereby leading Wisconsin’s dairy industry, to contribute more than $43.4 billion towards the state economy.

Known as “America’s Dairyland,” Wisconsin ranks No. 1 in the U.S. for cheese production, No. 2 for milk and is gaining strength in dried, condensed and evaporated milk and dairy supplies.

The dairy sector’s offshoot of jobs is similar to those of the potato and vegetable industry but also includes veterinarians and feed suppliers and dairy’s total jobs account for more than 40 percent of the 827,000 jobs in the agricultural sector.2

According to the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board, Inc. (WMMB), “Dairy’s multi-billion dollar economic impact is broadly dispersed throughout the state. Besides the direct economic contribution of farms and dairy-related companies, the dairy industry also uses machinery, trucks, fuel, financial services and other goods and services from local companies, generating additional ‘non-dairy’ jobs and income in the state. So, while residents may not realize it, the dairy industry impacts all sectors of Wisconsin’s economy.”2

WMMB also states that, “dairy infrastructure also plays a critical role in the health of Wisconsin’s economy. Because of Wisconsin’s extensive farm base, combined with agriculture’s industrial and service contribution, the overall impact of farming on Wisconsin’s economy is huge.” 2

RIGHT TO FARM

On July 11, 2012, the importance of the dairy industry’s contributions to Wisconsin’s financial strength was reinforced through a Wisconsin Supreme Court case, Adams v. Wisconsin Livestock Facilities Siting Rev. Bd., 2012 WI 85, in which the Wisconsin Supreme Court heard arguments on whether towns or cities can hold farms to tougher water-quality standards than state law requires.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court sided with the Larson family, a Wisconsin dairy farm family, against the town of Magnolia, concluding that the town cannot set pollution control measures for siting or expanding a Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFO) that are more strict than those measures laid out by the Wisconsin Legislature, which passed Wisconsin’s Livestock Facility Siting Law and Rule in 2004.2

This legislative action was necessary to retain the Wisconsin diminishing dairy farming processing industry, which is a major contributor to Wisconsin’s economy.

CHALLENGES

However, even with the major economic bearing that high capacity wells have had on our state, groundwater pumping by agricultural, municipal and industrial entities has endured increasing scrutiny by many governmental, private and environmental groups in the past few years.

Many of these groups claim that groundwater pumping is draining Wisconsin’s aquifers and the debate has loomed large in the Central Sands region. Scientific information and studies do not support those claims.

NEW GROUNDWATER ANALYSIS

Recently, GZA GeoEnvironmental, Inc. (GZA), founded in 1964, a highly respected consulting firm with a wealth of experience in impartial reports of groundwater and environmental conditions throughout the Midwest and many areas of the United States, completed an analysis of groundwater levels in the Central Sands region using well data provided by Roberts Irrigation and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR).

With over 500 professionals engaged in water issues, engineering and regulatory permitting, GZA provides tremendous depth and perspective in the development, management and protection of groundwater supplies and is a leader in groundwater services such as assessment of source and quality and remediation alternatives. GZA has gained the respect of the regulatory community for their impartial and high quality.

James F. Drought, P.H., Vice President and Principal Hydrogeologist with GZA and reviewer of the water level data in the Central Sands region, has over 25 years of professional consulting experience in the development, protection and management of groundwater supplies, groundwater soil and groundwater remediation, and litigation support services.

Drought received a Master of Science Degree in Contaminant Hydrogeology from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Physical Geography and Biology from Carroll College in Waukesha, Wisconsin.

Drought also serves as an Associate Faculty Member in the Environmental and Civil Engineering Department at the Milwaukee School of Engineering (MSOE), Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Drought is a Professional Hydrologist and a member and of National Ground Water Association, Wisconsin Ground Water Association, and Federation of Environmental Technologists.

SUBSTANTIATIONS

This new groundwater analysis from GZA reviews historic water level data from 58 Central Sands region wells dating back to the 1950s (Figure 1). According to James F. Drought, this initial analysis reveals that high capacity well pumping on the Central Sands wells he reviewed, has not adversely impacted aquifer storage, as the static water levels measured in 2014 remained relatively consistent in comparison to the static water levels measured during the initial installation of wells.

VOICES OF REASON

In March 2014, Bob Smail, WDNR water supply specialist, gave a presentation on The State of Groundwater Use and Management in Portage County to the Portage County board Groundwater Citizens Advisory Committee.

In that presentation, Bob Smail stated, “There is ample groundwater and the local economy is driven by groundwater sources. Groundwater supplies drinking water, water for the food processing, paper and other industries.”

Regarding groundwater withdrawals, Smail said, “There was a 35% increase in total withdrawals across the county from 2011 to 2012. To give context to the volume of water, spread equally over the land surface of the entire county, in 2011, the water would be l.5 inches deep and 2.5 inches in 2012. It sounds like a lot of water, but thinking in terms of rainfall, it would be a couple of good rainfalls.”

Smail explained further, “The numbers fall within a fairly small margin compared to precipitation in any given year. The variability in climate and weather are the biggest drivers in changes seen in hydrology on the landscape.”

Two additional charts (Figures 2 and 3) further illustrate that high capacity well pumping does not adversely impact aquifer storage.

The bar chart Portage County Rainfall Totals Versus Pumpage of High Capacity Wells in That Same Area (Figure 2), utilizes State of Wisconsin statistics. According to these statistics, in 2011, the rainfall total was 498 billion gallons while high capacity wells only pumped 21 billion gallons of water.

Although sources of water loss exist other than pumping, years 2012-2013 also showed that rainfall totals were far greater than gallons of water pumped by high capacity wells.

The Impacts of High Capacity Well Pumping on Stream Flow chart (Figure 3) depicts a Portage County stream east of Stevens Point that shows the impact of both agriculture and municipal high capacity well pumping on stream outflow feeding the Wisconsin and Mississippi river systems.

When high capacity wells for irrigation are pumping water from the deep aquifer during the growing season, water can be diverted from nearby streams to replenish the aquifer.

The degree of the diversion from the stream river system is dependent upon factors such as location and the distance of wells from streams, steam size and numerous site-specific geologic factors. Moving forward, all stakeholders will continue to work towards developing science-based solutions to help maintain stream flows.